The Experience Deficit

Why 9-9-6 Won’t Produce Good Ideas

I didn’t think I had been away that long.

But when I logged on to LinkedIn for the first time since mid-December, I found that my lower jaw had slipped an inch or so from neutral as I read about the latest fad from the same corner of the startup world that brought us such psychologically reversed concepts as “unlimited PTO” and setting oneself to “away.”

It’s called the 9-9-6.

If you have managed to avoid learning about it or perhaps thought it might refer to a pair of vintage Levi’s, 9-9-6 stands for 9am to 9pm, 6 days a week. In other words, a 72-hour workweek. We are told that it helps separate the truly dedicated from those merely hoping to support a life worth living.

Now, if I was to place a bet, I would have to wager this banal rebrand will be ditched as quickly as it cropped up. So, I won’t spend too much time deriding it as inhumane, nor will I propose that it’s merely pushback against the 4-day work week from the cult of the productivity-obsessed. I’ll leave that to the sharper tongues on r/LinkedInLunatics. Instead, I ‘d like to argue something more important: this Spartan approach to work is antithetical to the production of good ideas.

“To be fruitful in invention, it is indispensable to have a habit of observation and reflection.”

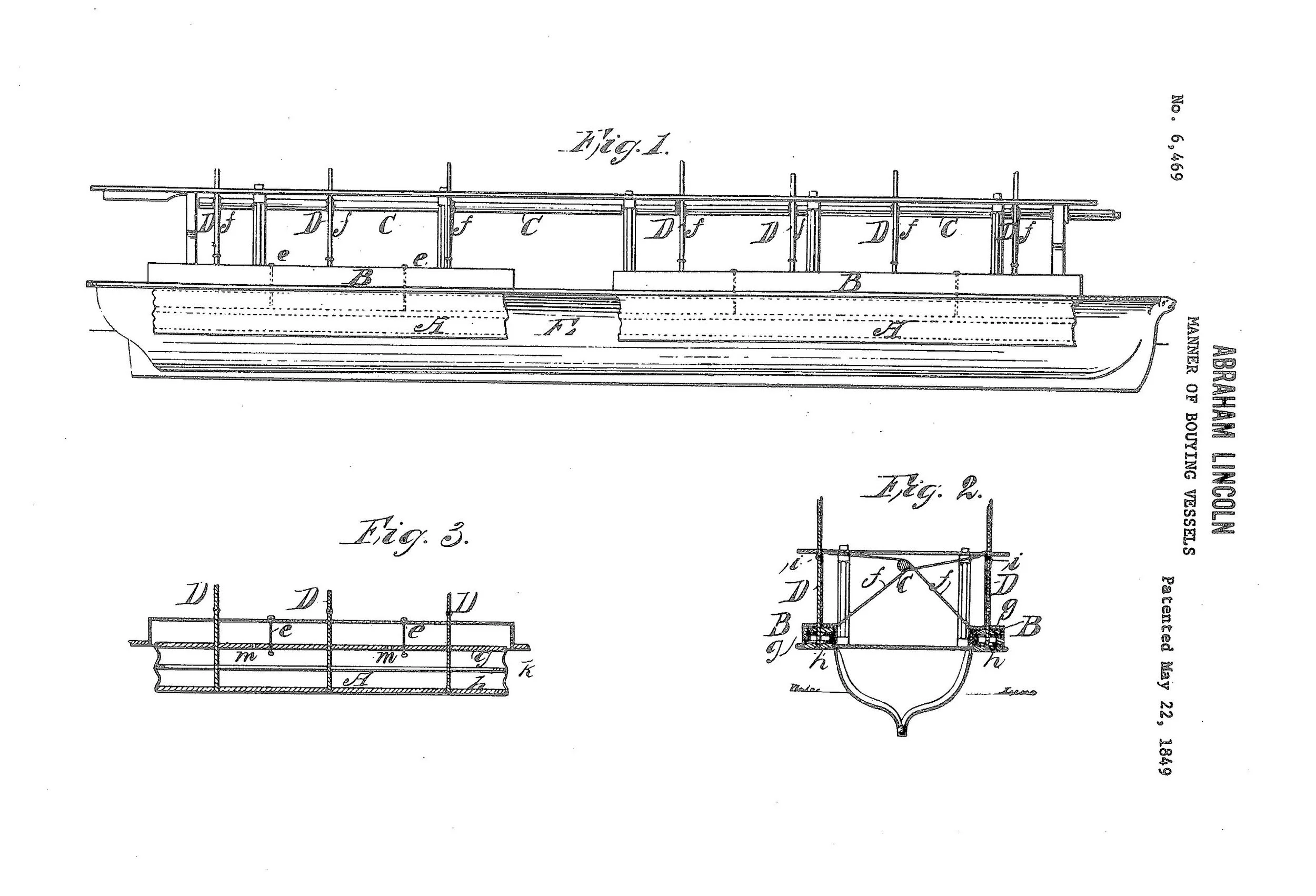

In addition to overseeing the deliverance, from bondage to freedom, of the largest number of human beings in the history of the United States, Abraham Lincoln was also a bit of an inventor. In 1849, a dozen years before he would ascend to the presidency, the forty-year-old Lincoln filed and was awarded Patent #6,469. The device for lifting boats over river shoals remains the only patent held by a U.S. President – including Jefferson.

Other than a scale model commissioned by Lincoln, the invention was never built or put into practical use, and at any rate it has long since been rendered obsolete. But that’s not important, what matters to us is how it came to be. After repeated flatboat trips along the Mississippi ended with the vessel running into something, old Abe, observing a recurring problem, reflected on it, and dreamt up a solution.

In fact, his interest in innovation would be carried to the highest office in the country. During the Civil War, Lincoln pushed for the military adoption of the telegraph, supported the deployment of balloon-based reconnaissance, and personally tested and approved the Spencer Repeating Rifle for Union troops. Clearly, this was not a man sealed away in his office, but someone alert and engaged with the outside world.

For all that has changed since 1849, one thing remains true: invention is not the result of effort alone. It requires exposure to the world, its people, its structures, its failures and successes.

Where Ideas Come From

Mark Twain, another veteran of the Mississippi, put it best: “All ideas are second-hand, consciously and unconsciously drawn from a million outside sources.” Now if that’s true, then how the hell is someone supposed to come up with any half-decent ideas if they never get out there and collide with a few of these sources?

Modern science agrees. The human brain, responsible for the conception, design, and fabrication of every artificial object in the solar system, is awe inspiring, and the manner in which this three-pound organ has accomplished all this is far more interesting – and more accessible – than any lame ex nihilo story about strokes of genius or divine inspiration.

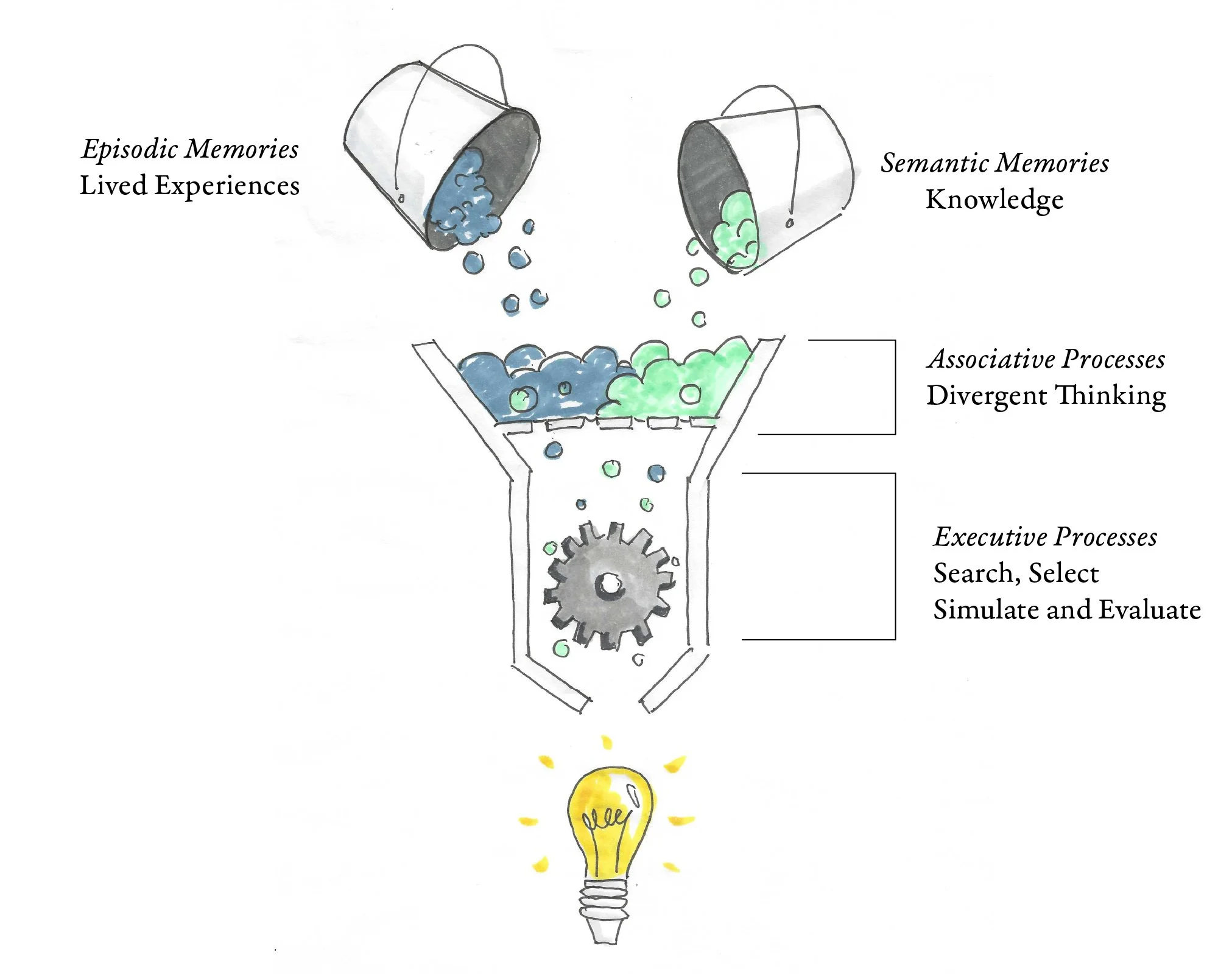

Novel ideas are the result of the interaction between memory, both personal experience and general knowledge, and the executive processes that search, sort, test and evaluate. Divergent thinking, followed by simulation and assessment. In other words, our wisest president proves himself again.

None of this should surprise a designer or an engineer. It makes great sense that the design process is merely the internal cognitive processes of problem solving made external. When done well, we mirror our brain; we gather divergent ideas, explore freely, and refine. Our sketches, models and prototypes amplify this thinking. By externalizing, we can expand upon it, pause and return to it, and invite others to join in the process, bringing their own collection of experience and knowledge.

An Experience Deficit

Scroll through LinkedIn and you will see dozens of authors sketching out the design process; sometimes representing it as a funnel, or maybe a double diamond or even a squiggly line smoothing out into a refined concept. They all correctly illustrate the process of a convergence of disparate element into an original and useful idea.

But it’s the first bit which seems to need some defending right now.

Because a good idea cannot converge without something to converge from.

I run into this often as teacher. I’ll assign a project to conceive of a new cooking utensil, only to discover many of the students have hardly ever cooked. Ask them to solve a daily problem, but their days consist primarily of class, screens, and what little else remains. Similarly, their internal library for form and mechanisms are thin. For this reason, we build the student foundation by asking them to draw a bajillion shapes, build countless models, visit the museum and reverse engineer old appliances.

Consulting designers face a similar challenge (or maybe it’s our best feature) in that we rarely enjoy repeated exposure to the same problem. Instead, we rely on a broad, generalist accumulation of experiences and solutions. In addition to research, we seek out analogues from our diverse exposure to materials, mechanisms, failures, solutions. We are forced to approach the problem by a different trail.

An employer can certainly demand that an employee sit down and not get up ‘til it’s done. But if they hope to have that employee dream up something new and worthwhile, they ought to try saying “now get out there and don’t come back till you have a few ideas!”

Yes, this requires discipline. And yes, young designers can suffer from the reverse problem of continuous exploration and never actually sitting down to do the work. But in a world increasingly online, increasingly looking to AI or Pinterest to find inspiration, creatives of all types ought to be pushing back hard against the confusion between being busy with being productive, being here with being present, and being exhausted with being innovative.

Now go explore.